Spectral sequence

In homological algebra and algebraic topology, a spectral sequence is a means of computing homology groups by taking successive approximations. Spectral sequences are a generalization of exact sequences, and since their introduction by Jean Leray (1946), they have become an important research tool, particularly in homotopy theory.

Contents |

Discovery and motivation

Motivated by problems in algebraic topology, Jean Leray introduced the notion of a sheaf and found himself faced with the problem of computing sheaf cohomology. To compute sheaf cohomology, Leray introduced a computational technique now known as the Leray spectral sequence. This gave a relation between cohomology groups of a sheaf and cohomology groups of the pushforward of the sheaf. The relation involved an infinite process. Leray found that the cohomology groups of the pushforward formed a natural chain complex, so that he could take the cohomology of the cohomology. This was still not the cohomology of the original sheaf, but it was one step closer in a sense. The cohomology of the cohomology again formed a chain complex, and its cohomology formed a chain complex, and so on. The limit of this infinite process was essentially the same as the cohomology groups of the original sheaf.

It was soon realized that Leray's computational technique was an example of a more general phenomenon. Spectral sequences were found in diverse situations, and they gave intricate relationships among homology and cohomology groups coming from geometric situations such as fibrations and from algebraic situations involving derived functors. While their theoretical importance has decreased since the introduction of derived categories, they are still the most effective computational tool available. This is true even when many of the terms of the spectral sequence are incalculable.

Unfortunately, because of the large amount of information carried in spectral sequences, they are difficult to grasp. This information is usually contained in a rank three lattice of abelian groups or modules. The easiest cases to deal with are those in which the spectral sequence eventually collapses, meaning that going out further in the sequence produces no new information. Even when this does not happen, it is often possible to get useful information from a spectral sequence by various tricks.

Formal definition

Fix an abelian category, such as a category of modules over a ring. A spectral sequence is a choice of a nonnegative integer r0 and a collection of three sequences:

- For all integers r ≥ r0, an object Er, called a sheet (as in a sheet of paper), or sometimes a page or a term,

- Endomorphisms dr : Er → Er satisfying dr o dr = 0, called boundary maps or differentials,

- Isomorphisms of Er+1 with H(Er), the homology of Er with respect to dr.

Usually the isomorphisms between Er+1 and H(Er) are suppressed, and we write equalities instead. Er+1 is sometimes called the derived object of Er.

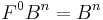

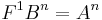

The most elementary example is a chain complex C•. C• is an object in an abelian category of chain complexes, and it comes with a differential d. Let r0 = 0, and let E0 be C•. This forces E1 to be the complex H(C•): At the i'th location this is the i'th homology group of C•. The only natural differential on this new complex is the zero map, so we let d1 = 0. This forces E2 to equal E1, and again our only natural differential is the zero map. Putting the zero differential on all the rest of our sheets gives a spectral sequence whose terms are:

- E0 = C•

- Er = H(C•) for all r ≥ 1.

The terms of this spectral sequence stabilize at the first sheet because its only nontrivial differential was on the zeroth sheet. Consequently we can get no more information at later steps. Usually, to get useful information from later sheets, we need extra structure on the Er.

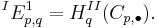

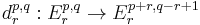

In the ungraded situation described above, r0 is irrelevant, but in practice most spectral sequences occur in the category of doubly graded modules over a ring R (or doubly graded sheaves of modules over a sheaf of rings). In this case, each sheet is a doubly graded module, so it decomposes as a direct sum of terms with one term for each possible bidegree. The boundary map is defined as the direct sum of boundary maps on each of the terms of the sheet. Their degree depends on r and is fixed by convention. For a homological spectral sequence, the terms are written  and the differentials have bidegree (-r,r-1). For a cohomological spectral sequence, the terms are written

and the differentials have bidegree (-r,r-1). For a cohomological spectral sequence, the terms are written  and the differentials have bidegree (r, 1 − r). (These choices of bidegree occur naturally in practice; see the example of a double complex below.) Depending upon the spectral sequence, the boundary map on the first sheet can have a degree which corresponds to r = 0, r = 1, or r = 2. For example, for the spectral sequence of a filtered complex, described below, r0 = 0, but for the Grothendieck spectral sequence, r0 = 2. Usually r0 is zero, one, or two.

and the differentials have bidegree (r, 1 − r). (These choices of bidegree occur naturally in practice; see the example of a double complex below.) Depending upon the spectral sequence, the boundary map on the first sheet can have a degree which corresponds to r = 0, r = 1, or r = 2. For example, for the spectral sequence of a filtered complex, described below, r0 = 0, but for the Grothendieck spectral sequence, r0 = 2. Usually r0 is zero, one, or two.

A morphism of spectral sequences E → E' is by definition a collection of maps fr : Er → E'r which are compatible with the differentials and with the given isomorphisms between cohomology of the r-th step and the (r + 1)-st sheets of E and E' , respectively. The category of spectral sequences is an abelian category.

Exact couples

The most powerful technique for the construction of spectral sequences is William Massey's method of exact couples. Exact couples are particularly common in algebraic topology, where there are many spectral sequences for which no other construction is known. In fact, all known spectral sequences can be constructed using exact couples. Despite this they are unpopular in abstract algebra, where most spectral sequences come from filtered complexes. To define exact couples, we begin again with an abelian category. As before, in practice this is usually the category of doubly graded modules over a ring. An exact couple is a pair of objects A and C, together with three homomorphisms between these objects: f : A → A, g : A → C and h : C → A subject to certain exactness conditions:

We will abbreviate this data by (A, C, f, g, h). Exact couples are usually depicted as triangles. We will see that C corresponds to the E0 term of the spectral sequence and that A is some auxiliary data.

To pass to the next sheet of the spectral sequence, we will form the derived couple. We set:

- d = g o h

- A' = f(A)

- C' = Ker d / Im d

- f' = f|A' , the restriction of f to A'

- h' : C' → A' is induced by h. It is straightforward to see that h induces such a map.

- g' : A' → C' is defined on elements as follows: For each a in A', write a as f(b) for some b in A. g'(a) is defined to be the image of g(b) in C'. In general, g' can be constructed using one of the embedding theorems for abelian categories.

From here it is straightforward to check that (A', C', f', g', h') is an exact couple. C' corresponds to the E1 term of the spectral sequence. We can iterate this procedure to get exact couples (A(n), C(n), f(n), g(n), h(n)). We let En be C(n) and dn be g(n) o h(n). This gives a spectral sequence.

Visualization

A doubly graded spectral sequence has a tremendous amount of data to keep track of, but there is a common visualization technique which makes the structure of the spectral sequence clearer. We have three indices, r, p, and q. For each r, imagine that we have a sheet of graph paper. On this sheet, we will take p to be the horizontal direction and q to be the vertical direction. At each lattice point we have the object  .

.

It is very common for n = p + q to be another natural index in the spectral sequence. n runs diagonally, northwest to southeast, across each sheet. In the homological case, the differentials have bidegree (−r, r − 1), so they decrease n by one. In the cohomological case, n is increased by one. When r is zero, the differential moves objects one space down or up. This is similar to the differential on a chain complex. When r is one, the differential moves objects one space to the left or right. When r is two, the differential moves objects just like a knight's move in chess. For higher r, the differential acts like a generalized knight's move.

Examples of spectral sequences

The spectral sequence of a filtered complex

A very common type of spectral sequence comes from a filtered cochain complex. This is a cochain complex C• together with a set of subcomplexes FpC•, where p ranges across all integers. (In practice, p is usually bounded on one side.) We require that the boundary map is compatible with the filtration; this means that d(FpCn) ⊆ FpCn+1. We assume that the filtration is descending, i.e., FpC• ⊇ Fp+1C•. We will number the terms of the cochain complex by n. Later, we will also assume that the filtration is Hausdorff or separated, that is, the intersection of the set of all FpC• is zero, and that the filtration is exhaustive, that is, the union of the set of all FpC• is the entire chain complex C•.

The filtration is useful because it gives a measure of nearness to zero: As p increases, FpC• gets closer and closer to zero. We will construct a spectral sequence from this filtration where coboundaries and cocycles in later sheets get closer and closer to coboundaries and cocycles in the original complex. This spectral sequence is doubly graded by the filtration degree p and the complementary degree q = n − p. (The complementary degree is often a more convenient index than the total degree n. For example, this is true of the spectral sequence of a double complex, explained below.)

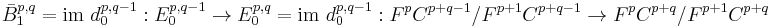

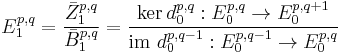

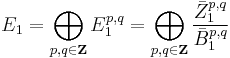

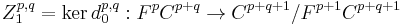

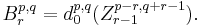

We will construct this spectral sequence by hand. C• has only a single grading and a filtration, so we first construct a doubly graded object from C•. To get the second grading, we will take the associated graded object with respect to the filtration. We will write it in an unusual way which will be justified at the E1 step:

Since we assumed that the boundary map was compatible with the filtration, E0 is a doubly graded object and there is a natural doubly graded boundary map d0 on E0. To get E1, we take the homology of E0.

Notice that  and

and  can be written as the images in

can be written as the images in  of

of

and that we then have

is exactly the stuff which the differential pushes up one level in the filtration, and

is exactly the stuff which the differential pushes up one level in the filtration, and  is exactly the image of the stuff which the differential pushes up zero levels in the filtration. This suggests that we should choose

is exactly the image of the stuff which the differential pushes up zero levels in the filtration. This suggests that we should choose  to be the stuff which the differential pushes up r levels in the filtration and

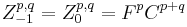

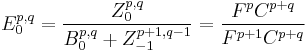

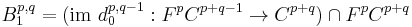

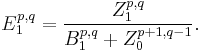

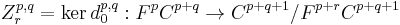

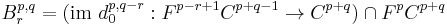

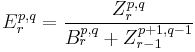

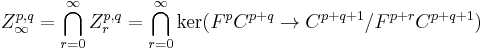

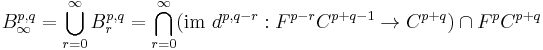

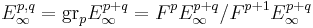

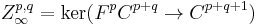

to be the stuff which the differential pushes up r levels in the filtration and  to be image of the stuff which the differential pushes up r-1 levels in the filtration. In other words, the spectral sequence should satisfy

to be image of the stuff which the differential pushes up r-1 levels in the filtration. In other words, the spectral sequence should satisfy

and we should have the relationship

For this to make sense, we must find a differential dr on each Er and verify that it leads to homology isomorphic to Er+1. The differential

is defined by restricting the original differential d defined on  to the subobject

to the subobject  .

.

It is straightforward to check that the homology of Er with respect to this differential is Er+1, so this gives a spectral sequence. Unfortunately, the differential is not very explicit. Determining differentials or finding ways to work around them is one of the main challenges to successfully applying a spectral sequence.

The spectral sequence of a double complex

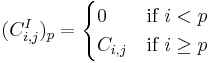

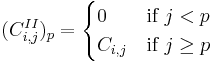

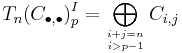

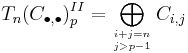

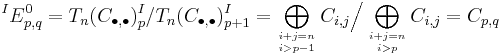

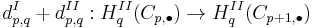

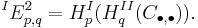

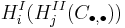

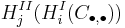

Another common spectral sequence is the spectral sequence of a double complex. A double complex is a collection of objects Ci,j for all integers i and j together with two differentials, d I and d II. d I is assumed to decrease i, and d II is assumed to decrease j. Furthermore, we assume that the differentials anticommute, so that d I d II + d II d I = 0. Our goal is to compare the iterated homologies  and

and  . We will do this by filtering our double complex in two different ways. Here are our filtrations:

. We will do this by filtering our double complex in two different ways. Here are our filtrations:

To get a spectral sequence, we will reduce to the previous example. We define the total complex T(C•,•) to be the complex whose n'th term is  and whose differential is d I + d II. This is a complex because d I and d II are anticommuting differentials. The two filtrations on Ci,j give two filtrations on the total complex:

and whose differential is d I + d II. This is a complex because d I and d II are anticommuting differentials. The two filtrations on Ci,j give two filtrations on the total complex:

To show that these spectral sequences give information about the iterated homologies, we will work out the E0, E1, and E2 terms of the I filtration on T(C•,•). The E0 term is clear:

To find the E1 term, we need to determine d I + d II on E0. Notice that the differential must have degree 1 with respect to n, so we get a map

Consequently, the differential on E0 is the map Cp,q → Cp,q−1 induced by d I + d II. But d I has the wrong degree to induce such a map, so d I must be zero on E0. That means the differential is exactly d II, so we get

To find E2, we need to determine

Because E1 was exactly the homology with respect to d II, d II is zero on E1. Consequently, we get

Using the other filtration gives us a different spectral sequence with a similar E2 term:

What remains is to find a relationship between these two spectral sequences. It will turn out that as r increases, the two sequences will become similar enough to allow useful comparisons.

Convergence, degeneration, and abutment

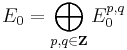

In the elementary example that we began with, the sheets of the spectral sequence were constant once r was at least 1. In that setup it makes sense to take the limit of the sequence of sheets: Since nothing happens after the zeroth sheet, the limiting sheet E∞ is the same as E1.

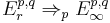

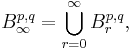

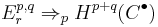

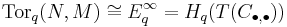

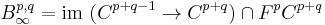

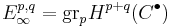

In more general situations, limiting sheets often exist and are always interesting. They are one of the most powerful aspects of spectral sequences. We say that a spectral sequence  converges to or abuts to

converges to or abuts to  if there is an r(p, q) such that for all r ≥ r(p, q), the differentials

if there is an r(p, q) such that for all r ≥ r(p, q), the differentials  and

and  are zero. This forces

are zero. This forces  to be isomorphic to

to be isomorphic to  for large r. In symbols, we write:

for large r. In symbols, we write:

The p indicates the filtration index. It is very common to write the  term on the left-hand side of the abutment, because this is the most useful term of most spectral sequences.

term on the left-hand side of the abutment, because this is the most useful term of most spectral sequences.

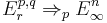

In most spectral sequences, the  term is not naturally a doubly graded object. Instead, there are usually

term is not naturally a doubly graded object. Instead, there are usually  terms which come with a natural filtration

terms which come with a natural filtration  . In these cases, we set

. In these cases, we set  . We define convergence in the same way as before, but we write

. We define convergence in the same way as before, but we write

to mean that whenever p + q = n,  converges to

converges to  .

.

The simplest situation in which we can determine convergence is when the spectral sequences degenerates. We say that the spectral sequences degenerates at sheet r if, for any s ≥ r, the differential ds is zero. This implies that Er ≅ Er+1 ≅ Er+2 ≅ ... In particular, it implies that Er is isomorphic to E∞. This is what happened in our first, trivial example of an unfiltered chain complex: The spectral sequence degenerated at the first sheet. In general, if a doubly graded spectral sequence is zero outside of a horizontal or vertical strip, the spectral sequence will degenerate, because later differentials will always go to or from an object not in the strip.

The spectral sequence also converges if  vanishes for all p less than some p0 and for all q less than some q0. If p0 and q0 can be chosen to be zero, this is called a first-quadrant spectral sequence. This sequence converges because each object is a fixed distance away from the edge of the non-zero region. Consequently, for a fixed p and q, the differential on later sheets always maps

vanishes for all p less than some p0 and for all q less than some q0. If p0 and q0 can be chosen to be zero, this is called a first-quadrant spectral sequence. This sequence converges because each object is a fixed distance away from the edge of the non-zero region. Consequently, for a fixed p and q, the differential on later sheets always maps  from or to the zero object; more visually, the differential leaves the quadrant where the terms are nonzero. The spectral sequence need not degenerate, however, because the differential maps might not all be zero at once. Similarly, the spectral sequence also converges if

from or to the zero object; more visually, the differential leaves the quadrant where the terms are nonzero. The spectral sequence need not degenerate, however, because the differential maps might not all be zero at once. Similarly, the spectral sequence also converges if  vanishes for all p greater than some p0 and for all q greater than some q0.

vanishes for all p greater than some p0 and for all q greater than some q0.

The five-term exact sequence of a spectral sequence relates certain low-degree terms and E∞ terms.

Examples of degeneration

The spectral sequence of a filtered complex, continued

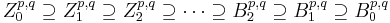

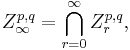

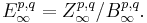

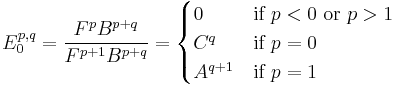

Notice that we have a chain of inclusions:

We can ask what happens if we define

is a natural candidate for the abutment of this spectral sequence. Convergence is not automatic, but happens in many cases. In particular, if the filtration is finite and consists of exactly r nontrivial steps, then the spectral sequence degenerates after the r'th sheet. Convergence also occurs if the complex and the filtration are both bounded below or both bounded above.

is a natural candidate for the abutment of this spectral sequence. Convergence is not automatic, but happens in many cases. In particular, if the filtration is finite and consists of exactly r nontrivial steps, then the spectral sequence degenerates after the r'th sheet. Convergence also occurs if the complex and the filtration are both bounded below or both bounded above.

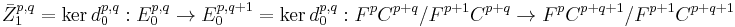

To describe the abutment of our spectral sequence in more detail, notice that we have the formulas:

To see what this implies for  recall that we assumed that the filtration was separated. This implies that as r increases, the kernels shrink, until we are left with

recall that we assumed that the filtration was separated. This implies that as r increases, the kernels shrink, until we are left with  . For

. For  , recall that we assumed that the filtration was exhaustive. This implies that as r increases, the images grow until we reach

, recall that we assumed that the filtration was exhaustive. This implies that as r increases, the images grow until we reach  . We conclude

. We conclude

,

,

that is, the abutment of the spectral sequence is the p'th graded part of the p+q'th homology of C. If our spectral sequence converges, then we conclude that:

Long exact sequences

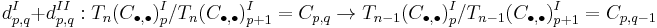

Using the spectral sequence of a filtered complex, we can derive the existence of long exact sequences. Choose a short exact sequence of cochain complexes 0 → A• → B• → C• → 0, and call the first map f• : A• → B•. We get natural maps of homology objects Hn(A•) → Hn(B•) → Hn(C•), and we know that this is exact in the middle. We will use the spectral sequence of a filtered complex to find the connecting homomorphism and to prove that the resulting sequence is exact. To start, we filter B•:

This gives:

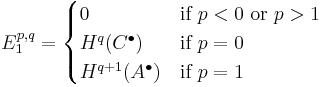

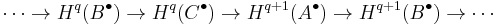

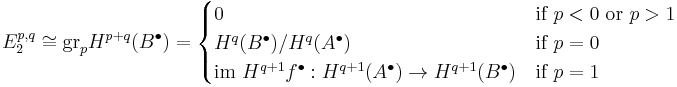

The differential has bidegree (1, 0), so d0,q : Hq(C•) → Hq+1(A•). These are the connecting homomorphisms from the snake lemma, and together with the maps A• → B• → C•, they give a sequence:

It remains to show that this sequence is exact at the A and C spots. Notice that this spectral sequence degenerates at the E2 term because the differentials have bidegree (2, −1). Consequently, the E2 term is the same as the E∞ term:

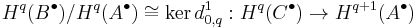

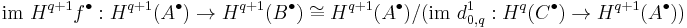

But we also have a direct description of the E2 term as the homology of the E1 term. These two descriptions must be isomorphic:

The former gives exactness at the C spot, and the latter gives exactness at the A spot.

The spectral sequence of a double complex, continued

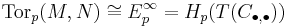

Using the abutment for a filtered complex, we find that:

In general, the two gradings on Hp+q(T(C•,•)) are distinct. Despite this, it is still possible to gain useful information from these two spectral sequences.

Commutativity of Tor

Let R be a ring, let M be a right R-module and N a left R-module. Recall that the derived functors of the tensor product are denoted Tor. Tor is defined using a projective resolution of its first argument. However, it turns out that Tori(M, N) = Tori(N, M). While this can be verified without a spectral sequence, it is very easy with spectral sequences.

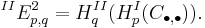

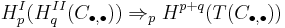

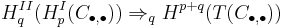

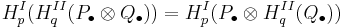

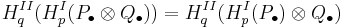

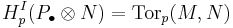

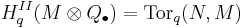

Choose projective resolutions P• and Q• of M and N, respectively. Consider these as complexes which vanish in negative degree having differentials d and e, respectively. We can construct a double complex whose terms are Ci,j = Pi ⊗ Qj and whose differentials are d ⊗ 1 and (−1)i(1 ⊗ e). (The factor of −1 is so that the differentials anticommute.) Since projective modules are flat, taking the tensor product with a projective module commutes with taking homology, so we get:

Since the two complexes are resolutions, their homology vanishes outside of degree zero. In degree zero, we are left with

In particular, the  terms vanish except along the lines q = 0 (for the I spectral sequence) and p = 0 (for the II spectral sequence). This implies that the spectral sequence degenerates at the second sheet, so the E∞ terms are isomorphic to the E2 terms:

terms vanish except along the lines q = 0 (for the I spectral sequence) and p = 0 (for the II spectral sequence). This implies that the spectral sequence degenerates at the second sheet, so the E∞ terms are isomorphic to the E2 terms:

Finally, when p and q are equal, the two right-hand sides are equal, and the commutativity of Tor follows.

Further examples

Some notable spectral sequences are:

- Adams spectral sequence in stable homotopy theory

- Adams–Novikov spectral sequence, a generalization to extraordinary cohomology theories.

- Atiyah–Hirzebruch spectral sequence of an extraordinary cohomology theory

- Bar spectral sequence for the homology of the classifying space of a group.

- Barratt spectral sequence converging to the homotopy of the initial space of a cofibration.

- Bloch–Lichtenbaum spectral sequence converging to the algebraic K-theory of a field.

- Bockstein spectral sequence relating the homology with mod p coefficients and the homology reduced mod p.

- Bousfield–Kan spectral sequence converging to the homotopy colimit of a functor.

- Cartan–Leray spectral sequence converging to the homology of a quotient space.

- Čech-to-derived functor spectral sequence from Čech cohomology to sheaf cohomology.

- Change of rings spectral sequences for calculating Tor and Ext groups of modules.

- Chromatic spectral sequence for calculating the initial terms of the Adams–Novikov spectral sequence.

- Connes spectral sequences converging to the cyclic homology of an algebra.

- EHP spectral sequence converging to stable homotopy groups of spheres

- Eilenberg–Moore spectral sequence for the singular cohomology of the pullback of a fibration

- Federer spectral sequence converging to homotopy groups of a function space.

- Fröhlicher spectral sequence starting from the Dolbeault cohomology and converging to the algebraic de Rham cohomology of a variety.

- Green's spectral sequence for Koszul cohomology

- Grothendieck spectral sequence for composing derived functors

- Hodge–de Rham spectral sequence converging to the algebraic de Rham cohomology of a variety.

- Hurewicz spectral sequence for calculating the homology of a space from its homotopy.

- Hyperhomology spectral sequence for calculating hyper homology.

- Kunneth spectral sequence for calculating the homology of a tensor product of differential algebras.

- Leray spectral sequence converging to the cohomology of a sheaf.

- Leray–Serre spectral sequence of a fibration

- Lyndon–Hochschild–Serre spectral sequence in group (co)homology

- May spectral sequence for calculating the Tor or Ext groups of an algebra.

- Miller spectral sequence converging to the mod p stable homology of a space.

- Milnor spectral sequence is another name for the bar spectral sequence.

- Moore spectral sequence is another name for the bar spectral sequence.

- Quillen spectral sequence for calculating the homotopy of a simplicial group.

- Rothenberg–Steenrod spectral sequence is another name for the bar spectral sequence.

- Spectral sequence of a differential filtered group: described in this article.

- Spectral sequence of a double complex: described in this article.

- Spectral sequence of an exact couple: described in this article.

- Universal coefficient spectral sequence

- van Est spectral sequence converging to relative Lie algebra cohomology.

- van Kampen spectral sequence for calculating the homotopy of a wedge of spaces.

References

- Hatcher, Allen (PDF), Spectral Sequences in Algebraic Topology, http://www.math.cornell.edu/~hatcher/SSAT/SSATpage.html

- Leray, Jean (1946), "L'anneau d'homologie d'une représentation", Les Comptes rendus de l'Académie des sciences 222: 1366–1368

- Leray, Jean (1946), "Structure de l'anneau d'homologie d'une représentation", Les Comptes rendus de l'Académie des sciences 222: 1419–1422

- Koszul, Jean-Louis (1947), "Sur les opérateurs de dérivation dans un anneau", Les Comptes rendus de l'Académie des sciences 225: 217–219

- Massey, William S. (1952), "Exact couples in algebraic topology. I, II", Annals of Mathematics. Second Series (Annals of Mathematics) 56 (2): 363–396, doi:10.2307/1969805, JSTOR 1969805

- Massey, William S. (1953), "Exact couples in algebraic topology. III, IV, V", Annals of Mathematics. Second Series (Annals of Mathematics) 57 (2): 248–286, doi:10.2307/1969858, JSTOR 1969858

- McCleary, John (2001), A User's Guide to Spectral Sequences, Cambridge Studies in Advanced Mathematics, 58 (2nd ed.), Cambridge University Press, doi:10.2277/0521567599, ISBN 978-0-521-56759-6, MR1793722

- Mosher, Robert; Tangora, Martin (1968), Cohomology Operations and Applications in Homotopy Theory, Harper and Row, ISBN 978-0-06-044627-7

- Weibel, Charles A. (1994), An introduction to homological algebra, Cambridge Studies in Advanced Mathematics, 38, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-55987-4, OCLC 36131259, MR1269324